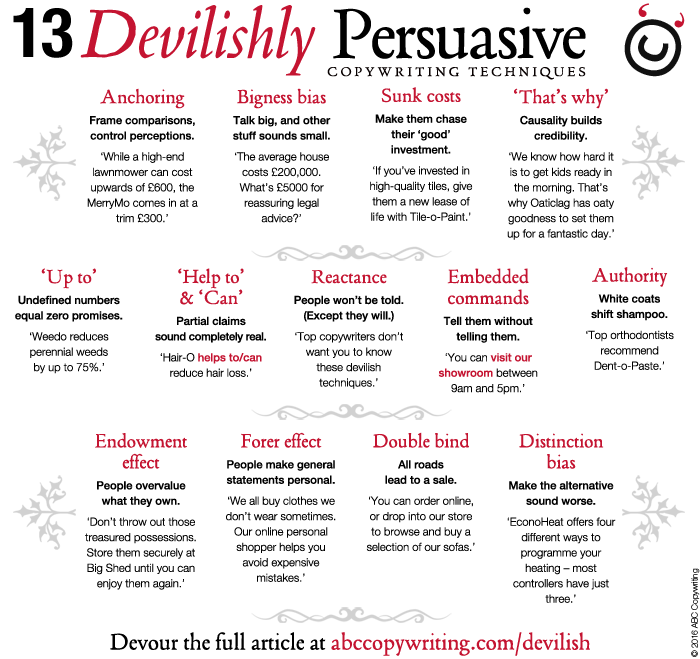

Thirteen devilishly persuasive copywriting techniques

Engagement. Permission. Storytelling. What’s wrong with marketers these days? It’s time to drop the sanctimony and fulfil our evil destiny: making people buy stuff they really don’t need. Let me show you how with these thirteen wickedly effective techniques straight out of Satan’s own sale-stealing playbook – just in time for Hallowe’en.

Anchoring

Frame comparisons, control perceptions.

Maybe the product you’re writing about isn’t too bad – but the price is outrageous.

Turns out, if you find a way to say a big number, it’ll make anything else your reader hears sound small. The psychs call it ‘anchoring’.

Let’s say you’re selling, I don’t know, lawnmowers. First you talk about prestige models costing upwards of £600. Then, when you reveal that your cheapo knock-off costs ‘just’ £300, it actually sounds reasonable. Compared to a number that, for all they know, you just made up.

While a high-end lawnmower can cost upwards of £600, the MerryMo comes in at a trim £300.

Bigness bias

Talk big, and other stuff sounds small.

Imagine you’re getting legal advice on divorcing your dull-as-ditchwater husband. The solicitor says it will cost £5000. Sounds a lot, right? Maybe you can put up with watching Top Gear after all.

Now imagine you’re buying a new house – one your husband won’t be inhabiting – for £200,000. The legal costs for this will also be £5000. But next to the £200k, the amount sounds a lot more reasonable.

It’s still the same money. It took you the same time to earn and could buy exactly the same goods or services elsewhere. But in the context of a much bigger purchase, it looks small.

The average UK house sells for £200,000. What’s £5000 for the reassurance of professional legal help?

Sunk costs

Make them chase their ‘good’ investment.

A sunk cost is money that’s been spent and can’t be recovered. People tend to ‘honour’ their sunk costs even when it would make more sense to forget them and move on, because in their minds that would be ‘wasting’ the money they spent before.

The classic example is buying a theatre ticket in advance, then falling ill on the day of the performance. Many people will ‘protect their investment’ by going to the show even if it makes them feel worse, to avoid ‘wasting’ the cost of the ticket. In reality, the money is gone no matter what they do, and they’d be happier staying home.

Let’s say you’re selling a tile paint that lets people change the colour of their bathroom without retiling. Deep down, both you and the reader know that it would be better to rip off the tiles and start again. But that would be ‘wasting’ the old tiles:

If you’ve invested in high-quality tiles, give them a new lease of life with Tile-o-Paint, the cheaper alternative to retiling.

Now, instead of throwing good money after bad, they’re making a canny purchase that lets them have their cake and eat it. And their sunk costs have kept your sale very much afloat.

‘That’s why’

Causality builds credibility.

If the copywriter’s brain is a box of tools, ‘that’s why’ is the adjustable spanner. There’s almost nowhere you can’t drop it in for instant credibility.

First, soften them up with some grovelling empathy:

We know how hard it is to get kids ready in the morning…

Then hit them with the arbitrary segue into the product:

…That’s why we’ve created new Oaticlag, with plenty of rich oaty goodness to set them up for a fantastic day.

See how easy that was? And it doesn’t even matter whether the product really is the answer or not – ‘that’s why’ puts it in the box seat regardless.

‘Up to’

Undefined numbers equal zero promises.

Nothing gives your copy some much-needed substance quite like cold, hard data. If you can measure it, it must be real. But what if your stats are writing a cheque the product just can’t cash?

In this situation, ‘up to’ is your friend, letting you make a big-sounding claim without actually saying anything at all. For example:

Weedo reduces perennial weeds by up to 75%

‘Up to 75%’ means ‘Between 0% and 75%’. So you’re not really promising anything – just gesturing vaguely in the direction of an unquantified benefit. But it sounds fantastic.

‘Up to’ plays on overconfidence, or irrational optimism. Tell people their results will be in a range and they immediately assume their results will be near the top. It’s human nature.

‘Help to’ and ‘can’

Partial claims sound completely real.

Making concrete claims is always a tough one, particularly if the product’s rubbish. Don’t worry, though – there’s a way to dramatically downgrade the benefits you’re claiming at almost no rhetorical cost.

Check out the difference between:

Hair-o reduces hair loss

and

Hair-o helps to reduce hair loss

To the inattentive ear, they sound almost the same, but there’s a world of difference in meaning. In the first line, Hair-o takes all the credit. But in the second, its contribution could be tiny. Sure, it’s ‘helping’ – but its ‘help’ could be as helpful as the help that a three-year-old offers with the washing up.

Now check out ‘can’:

Hair-o can reduce hair loss

Now Hair-o’s doing even less than before – maybe even nothing. All you’re saying is that it can reduce hair loss. The circumstances where it can might be vanishingly unlikely, perhaps requiring the customer to do dozens of additional things. Doesn’t matter – it still can do what you’re saying. (Even if it probably won’t.)

Reactance

People won’t be told. (Except they will.)

If you’ve ever tried to get a small child ready to leave the house, you already know about reactance: the tendency to do the opposite of what we’re told, even when it would benefit us.

Politicians know all about reactance. As long as they can portray their policies as a rebellion against somebody – Brussels bureaucrats, East Coast liberals – they can turn a vote for them into a ‘protest’. Hey, voter, ‘they’ don’t want you to do such-and-such. Are you going to let them push you around? Take back control!

If you can set up a situation where your reader expresses reactance by buying into your message, you’re on to a winner. For example:

You might not believe this, but Wireco broadband could be five times faster than your current service.

This goads the reader into ‘proving you wrong’ by swallowing your claim. You dared them not to believe it, and they only went ahead and believed it anyway. Those tiresome online ads about a tooth-whitening treatment that ‘dentists don’t want you to know about’ pull the same trick.

You can also try a soft-pedal approach:

The benefits of Waxo are crystal clear. But of course, the final decision is yours.

‘What do you mean?’ you reader thinks. ‘Why wouldn’t I buy it? Do you think I’m stupid?’

Of course not. But hey, you did walk right into my reactance trap.

Embedded commands

Tell them without telling them.

Ever felt like just straight-out telling the reader what to do? Well, now you can – provided you can come up with a moderately contrived sentence. And I just know that you can.

An embedded command is a sentence within a sentence, usually formed as an imperative. For example:

You can visit our showroom any time between 9am and 5pm.

Making the parent sentence relaxed and permissive takes the sting out of being pushed around. Turns out you really can pee on people’s shoes and tell ’em it’s raining. Now, imagine how surprised you’ll be when you make me a cup of tea.

Authority

White coats shift shampoo.

Persuading someone to buy one-on-one can be a struggle. But with an authoritative ally backing you up, the fight becomes gratifyingly unfair.

Ideally, the audience will have heard of the authority you cite. But it doesn’t really matter either way. As long as they have an official-sounding title or qualification, it’ll probably be enough.

Top orthodontists recommend Dent-o-Paste.

Shallow? Cheap? No doubt. But it works, because people are cognitive misers – give them some prima facie signifiers to work with and they probably won’t bother to question them. That’s the secret of confidence tricksters and cynical copywriters down the ages – and now it’s yours.

The endowment effect

People overvalue what they own.

If you’ve ever helped someone move house, you’ve seen the endowment effect in action. They’re packing up boxes of useless old junk they should really throw away. But to them, it’s stuff they’ve paid good money for; it might come in handy one day. So they lug it all over to their new house, where it will sit in the loft, untouched, for decades on end, until they die and their kids dump the lot without a second thought.

Naturally, this presents opportunities for the manipulative copywriter.

Moving home? Short of space? Don’t throw out those treasured possessions. Store them securely at Big Shed until you can enjoy them again.

The endowment effect means people will pay more to retain a thing they own than to get an identical thing owned by someone else – even if they’ve only owned it for a few minutes, or there’s no rational reason for them to want it. That’s because giving up something they have feels like a loss, and people hate losing almost as much as they hate thinking rationally.

Time-limited trials, test-drives and free-to-play videogames all play on the endowment effect. Once people are hooked, they feel that the product, car or game is already theirs, even if they haven’t paid for it. And then they will pay to hang on to it.

To trigger the endowment effect, make liberal use of ‘your’ to emphasise possession, while laying it on extra thick about the terrible danger of losing out on something wonderful:

We hope you enjoyed your free trial of Lawnmower World. To make sure you continue to receive your copy every month, fill out the form below and send it to us by 30 September. Remember, if you don’t act, your subscription will end this month.

The Forer effect

People make general statements personal.

Psychologist Bertram Forer gave a group of students what they thought was a personal profile, but was in fact a list of 13 statements that were the same for all of them. They still marked it 4.26 out of 5 for accuracy, on average.

It worked because the statements were so vague that anyone could identify with them. For example:

You have a great need for other people to like and admire you.

You have a tendency to be critical of yourself.

At times you have serious doubts as to whether you have made the right decision or done the right thing.

Forer’s most universal statements began ‘At times…’ That’s because people don’t have personality types, but personality states.

So if you’re hoping to build empathy with the reader, it’s far more effective to key into something they’ve probably thought or felt at some point, rather than trying to cram them into a persona:

From time to time, you probably wonder if you’re really saving enough for retirement. Use our simple annuity calculator to see what income you can expect.

I guess we’ve all wanted to write something that engaging at one time or another.

The double bind

All roads lead to a sale.

A double bind presents as a choice between two alternatives, but in reality both paths lead to the same destination. For example:

You can order online, or drop into our store to browse and buy a selection of our sofas.

Here, the reader has two choices, but both entail ultimately making a purchase. The idea is to present alternatives at one level of behaviour (choose how to purchase) that amount to the same thing at a higher level (make a purchase). The option not to buy is excluded by implication.

Distinction bias

Make the alternative sound worse.

Use distinction bias by juxtaposing your product with an alternative option and emphasising some distinction between them.

The alternative doesn’t have to be a competing product, or even exist in the real world. It just has to offer less value than whatever you’re selling.

You choose the basis of comparison to suit your agenda. For example:

The EconoHeat offers four different ways to programme your heating – most controllers have just three.

Readers should really be asking themselves how many heating-programming methods is enough, or whether the number is relevant at all. But if you frame their decision as a choice between two alternatives, one of which seems worse, they’ll choose the ‘better’ one every time.

Comments (1)

Comments are closed.

This article is a great reminder of techniques I already knew and added a couple with a fresh twist. Thanks. I am glad I found it. I will incorporate these on my website. http://propertyinvestorstoday.com