It’s OK to sell things

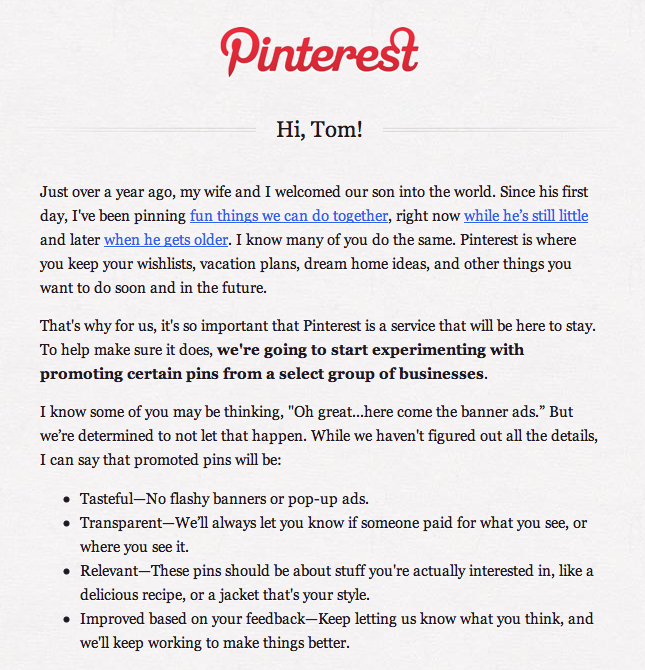

A few days ago, I received this email from Pinterest (transcript below).

Hi, Tom!

Just over a year ago, my wife and I welcomed our son into the world. Since his first day, I’ve been pinning fun things we can do together, right now while he’s still little and later when he gets older. I know many of you do the same. Pinterest is where you keep your wishlists, vacation plans, dream home ideas, and other things you want to do soon and in the future.

That’s why for us, it’s so important that Pinterest is a service that will be here to stay. To help make sure it does, we’re going to start experimenting with promoting certain pins from a select group of businesses.

I know some of you may be thinking, “Oh great…here come the banner ads.” But we’re determined to not let that happen… [continues]

Ostensibly, this email an open, heartfelt message from one user of a service to another. In reality, it’s profoundly disingenuous. (Forget the split infinitive on ‘to not let’, we’ve got bigger fish to fry.)

Taken at face value, it implies that Ben Silbermann just kinda got Pinterest going with his good buddies because he wanted to help people, y’know, share their memories and stuff. A couple years later, Ratuken knocked on the door and gave them a suitcase containing $100m, presumably just because they thought the site was hella cool.

But now Ben’s a daddy, and that sure made him think differently about a whole bunch of stuff. So, even though it’s a royal pain in the ass, he’s gonna have to host some ads. Because if he doesn’t, Pinterest might have to shut down!

Capitalists gonna capitalise

Cut the crap, Silbermann. People don’t start businesses to help people. The word for a philanthropic business is ‘charity’. Ultimately, whatever business founders say about their mission, values or whatever, at the end of the day they want that cheddar.

What’s wrong with that? Absolutely nothing. I vote Labour, but that doesn’t mean I work for free. When I deliver value, I want value in return. Such are the social contracts on which our economy is built.

For some reason, though, some brands seem hell-bent on obscuring this basic truth – not with the wit and invention of the great masters, but with sop and schmaltz.

At some point in the last decade, it became fashionable, if not expected, for brands to act like our BFFs. If we wanted to trace the origins of this trend, we might point to the rise of social media, the financial crash or the pioneering tone of Innocent Drinks. But whatever the reason, everybody is now at it.

We know… that’s why

At the level of word choice, a very common ‘brand as friend’ technique is ‘we know… that’s why’, which Pinterest uses in its email. The key passages are ‘I know many of you…’ and ‘That’s why for us…’

In this construction, the ‘we know’ statement stakes a claim to some situation, emotion or value that is familiar to the customer and supposedly shared or understood by the brand. There then follows a bait-and-switch, pivoted on ‘that’s why’, that positions a product or service – or, as here, the degrading of a service – as a thoughtful, heartfelt response to whatever the customer is doing or feeling. (I moaned about ‘that’s why’ here and Kevin Mills took it to the next level here.)

This technique is about edging up the emotional food chain to get closer to what customers ‘really value’. Using a cleaning product isn’t just about getting things clean, it’s about protecting your family. Getting a mortgage isn’t just about securing a loan, it’s about having the home you deserve. And using Pinterest isn’t just about collecting pictures of prams, it’s about curating your future.

The New Honesty

In my piece on wackywriting, I speculated whether the British Airways rebrand (‘To Fly, To Serve’) might herald the birth of the New Formality. Increasingly, though, I think what we really need is the New Honesty – a regained sense of perspective about what people really want from brands.

We don’t think about the big emotional themes of our lives all the time, only in moments of reflection, and alluding to them isn’t necessarily a shortcut to our affections. Nor are we constantly looking for someone to empathise with our deepest emotions, and the cynical attempt to do so is crass and intrusive. All we really need is someone to take our problems away – just like in real life.

‘You do the school run and I’ll make the tea.’ There’s no need for me to say how much I care about your tiredness, your back pain or how busy you are at work. Which is good, because, to be honest, I don’t. I just want to get everything done, sit down and open the Cab Sauv – as do you. So let’s make a nice, clear, mutually beneficial deal, unsullied by plaintive whimpering or emotional blackmail.

Entitlement culture

In the world of online startups, such transactional honesty is verboten. The reasons for this include the pervasive culture of ‘it must be free’ entitlement, youthful firms run by youthful founders and an eye-watering pace of change, all of which mean that any emotional foothold in the consumer’s heart is like gold dust.

The result is an uneasy compromise between the benefits of using a platform and the inevitable inconveniences of not paying for it (such as surveillance and ads), tempered by whatever affection and loyalty the brand can manage to drum up among its user base. It’s a shady, unquantifiable deal, very far from a simple ‘product for money’ purchase.

It doesn’t have to be that way. In this piece for Econsultancy, I argued that Twitter should make a small charge for its service, or adopt a ‘freemium’ model, like Spotify’s, where users can pay for an ad-free experience. Predictably, I got some heat in the comments, although a few people were brave enough to agree.

The truth is that if you don’t pay for a digital platform with money, you pay with ad clicks, personal data or both. That’s the reality behind the faux-philanthropy and relentless chumminess of tech startups. And while people may not have been totally clear on that five years ago, I’m pretty sure they are now. So why not use a tone of voice that gives them credit?

Customers may be emotional, but they aren’t stupid. We can’t buy them off or hoodwink them by talking about some emotion we hope they feel. We can only offer them a deal that they take or leave. And if they don’t buy our message, why would they buy anything else?

Tags: Ben Silbermann, Bill Bernbach, digital entitlement, freemium, Pinterest, Twitter