Copywriting with The Beatles

I love The Beatles, having listened to them pretty much all my life. Every time I return to the songs, they seem to have improved somehow – but maybe I’ve just learned to hear them better.

My most recent period of obsession was prompted by reading Ian Macdonald’s superlative study of The Beatles’ records, Revolution in the Head, which analyses music, lyrics and recordings in illuminating detail. (This post owes a lot to the book.) And when I started thinking about the Fab Four’s songs in relation to my work, it seemed there were plenty of interesting parallels.

Should I work through a few examples? If you want me to, I will…

From me to you

Thirty-nine of the titles of The Beatles’ 187 original songs contain the word ‘you’ or ‘your’. ‘You’ is instantly engaging, pulling the listener in and inviting them to inhabit the scenarios being described.

In 1963, the thought of inhabiting any sort of scenario with a Beatle sent their female fans (and Brian Epstein) into a frenzy – a fact John and Paul exploited in songs like ‘Thank You Girl’. Later in the decade, as they explored more countercultural themes, their ‘yous’ became more universal, as in ‘Baby, You’re A Rich Man’, ‘All You Need Is Love’ and ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’ (‘Look at you all…’).

In 1963, the thought of inhabiting any sort of scenario with a Beatle sent their female fans (and Brian Epstein) into a frenzy – a fact John and Paul exploited in songs like ‘Thank You Girl’. Later in the decade, as they explored more countercultural themes, their ‘yous’ became more universal, as in ‘Baby, You’re A Rich Man’, ‘All You Need Is Love’ and ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’ (‘Look at you all…’).

Copywriters who want to engage their audience do the same thing, using ‘you’ to involve and engage them in the message. ‘You’ implicitly positions the message as being relevant to the reader – although the rest of the writing must deliver on that promise. There’s nothing worse than shouting ‘hey you!’ and then having nothing to say.

I want to tell you

One step on from addressing the listener is giving them an instruction. A good many Beatles numbers have commands as their titles: ‘Hold Me Tight’, ‘Don’t Bother Me’, ‘Let It Be’, ‘Ask Me Why’ and others.

John’s lyrics often use commands to bring the listener into his inner world:

Picture yourself in a boat on a river

With tangerine trees and marmalade skies

‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’Let me take you down ’cause I’m going to Strawberry Fields

‘Strawberry Fields Forever’

Using the imperative as the very first word of the song shows John’s directness as a writer, and perhaps also his brusqueness as a person. His greatest lyrical command (post-Beatles) was probably the single word ‘Imagine’ – a call to think beyond our material circumstances that inspired listeners worldwide.

Paul, more urbane and less visionary than John, typically uses imperatives when reaching for a more personal sense of immediacy or intimacy. His commands are more like invitations into a particular emotional perspective…

Treasure these few words ’til we’re together

Keep all my love forever

P.S. I love you

‘P.S. I Love You’Think of what you’re saying

You can get it wrong and still you think that it’s all right

‘We Can Work It Out’

…or a realistic visual tableau:

Look at him working

Darning his socks in the night when there’s nobody there

‘Eleanor Rigby’

Copywriters most often use imperatives in the call to action. But as these examples show, they can help the writing along in other ways too – most often, by encouraging the reader to see or think a certain way. Commands can also convey immediacy, for example by inviting the reader to read on.

Is there anybody going to listen to my story

Many Beatles lyrics derive their fascination and longevity from their masterful dramatic tension, development and release. In other words, they tell a story.

‘She Loves You’ uses snippets of third-party gossip to sketch a precarious love affair in its verses before resolving it, gloriously, in the chorus. ‘Norwegian Wood’ paints a more surreal picture of a romantic encounter, saying far more by explaining far less and ending in enigmatic ambiguity.

Paul, in particular, loves to tell a story in his lyrics, with results that are coldly compelling (‘For No One’), genuinely moving (‘She’s Leaving Home’) or downright embarrassing (‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’, ‘O-Bla-Di, O-Bla-Da’).

Paul, in particular, loves to tell a story in his lyrics, with results that are coldly compelling (‘For No One’), genuinely moving (‘She’s Leaving Home’) or downright embarrassing (‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’, ‘O-Bla-Di, O-Bla-Da’).

The concept of brand or corporate storytelling has perhaps been overdone in recent years, the imposition of story on a marketing task sometimes seeming to complicate rather than clarify. But it is true that story keys into our most basic ways of thinking, making it a powerful tool for the copywriter. And it’s also true that many value propositions can be most concisely expressed as a story – often, the progression from problem to solution via the benefits of a product.

There’s certainly no harm in considering whether the narrative form can add value, whether you’re writing an informative ‘About us’ page, a detailed case study or a slogan that tells a story with just a few words.

Tell me what you see

Imagery plays an important part in many Beatles numbers. When the occasion demanded, Paul was capable of crafting timeless metaphors, such as those in ‘Blackbird’, ‘The Fool On The Hill’ or ‘The Long And Winding Road’, although he reserved most of his lyric-pictures for his sentimental observations of everyday life and ordinary people (‘Penny Lane’, ‘Lovely Rita’, ‘Eleanor Rigby’, ‘She’s Leaving Home’). The rococo imagery of his later songs (‘She Came In Through The Bathroom Window’) foreshadowed the headlong descent into irrelevance of his Lennonless solo/Wings career, ‘fatally neglecting meaning and expression’ as Ian Macdonald puts it.

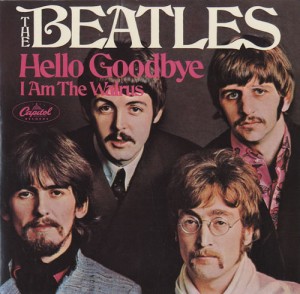

The first Beatle to try LSD, John was also the first to capture his psychedelic visions in song (‘Tomorrow Never Knows’). As the drug’s effects combined with his natural rebelliousness, his songwriting developed into using ‘random’ imagery as a weapon to prise open the closed minds of the ‘straight’ establishment (‘I Am The Walrus’, ‘Come Together’, ‘Happiness Is A Warm Gun’).

The first Beatle to try LSD, John was also the first to capture his psychedelic visions in song (‘Tomorrow Never Knows’). As the drug’s effects combined with his natural rebelliousness, his songwriting developed into using ‘random’ imagery as a weapon to prise open the closed minds of the ‘straight’ establishment (‘I Am The Walrus’, ‘Come Together’, ‘Happiness Is A Warm Gun’).

The most obvious way for imagery and analogy to figure in the copywriter’s work is when developing ‘copy and concept’ ideas for advertisements. The right combination of words and pictures dramatises the key benefit of a product or service, bringing it to the reader’s attention more powerfully than a literal ‘sales pitch’ ever could. But vivid metaphors can figure in any type of writing, as long as they serve to clarify the meaning as well as they did for the Beatles.

I think er no I mean er yes but it’s all wrong

The Beatles’ early lyrics either dealt in simple emotions (‘From Me To You’, ‘P.S. I Love You’) or hid whatever depth they had behind genre conventions (the self-conscious country and western of ‘I’m A Loser’) or humour (‘Drive My Car’, with its jokey punchline).

Inspired by Dylan (and their discovery of cannabis in his New York hotel room), Beatles lyrics became more personal, vivid and arresting from 1964 onwards. Sometimes, however, this was due not so much to deliberate experiment, but to incorporating mistakes.

If she’s gone I can’t go on

Feeling two foot small

‘You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away’

The line as written was ‘two foot tall’. John fluffed the vocal but let the mistake stand, saying ‘Leave that in, the pseuds’ll love it.’ He relished winding up those who over-analysed his lyrics, but he surely also recognised that the mistake was better than the original. One tiny change made a stock phrase surreally evocative and memorable.

Some kind of solitude is measured out in you

You think you know me but you haven’t got a clue

‘Hey Bulldog’

This time, the original line was ‘measured out in news’, but Paul improved it by pretending to have misread John’s handwriting.

This time, the original line was ‘measured out in news’, but Paul improved it by pretending to have misread John’s handwriting.

The lesson for copywriters? Be open to the workings of chance, which can open a direct line to your unconscious. Don’t be afraid to make an improvement just because it arrived by accident.

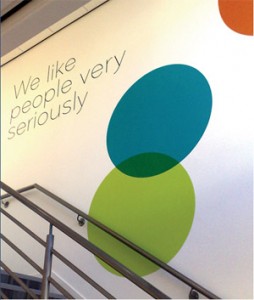

Copywriter Oliver Wingate wrote his tagline for Pure Resourcing Solutions this way. Working from the client’s brief to market them as a ‘people company’, he doodled the line ‘We take people very seriously’. When he glanced back at his work, ‘take’ resembled ‘like’ and the line was written: ‘We like people very seriously’. The client loved it, and emblazoned it on the wall of their offices (see image, right).

Half of what I say is meaningless

Conscious experiment also played an important role in The Beatles’ songwriting. For Paul, who often worked within the bounds of stylistic convention (‘Oh! Darling’) or even pastiche (‘Honey Pie’), formal transgression was rare and usually with a clear aesthetic aim, as with these breathless overlapping sentences expressing love at first sight:

I’ve just seen a face I can’t forget

The time and place where we just met

‘I’ve Just Seen A Face’

John, on the other hand, went out of his way to bend the rules of songwriting and indeed grammar as far as he could, just to see where it took him:

I am he as you are he as you are me and we are all together

‘I Am The Walrus’

What does this line mean? To some, perhaps, it’s nonsense. To others, a perfect précis of the whole ethos of 1967. And in between, it carries a whole range of other meanings, each as individual as the person hearing the song. By abandoning clarity, the lyric paradoxically becomes far more powerful. (And although I’m glad it will never happen, it would be a great slogan for a social network site or a mobile operator.)

What does this line mean? To some, perhaps, it’s nonsense. To others, a perfect précis of the whole ethos of 1967. And in between, it carries a whole range of other meanings, each as individual as the person hearing the song. By abandoning clarity, the lyric paradoxically becomes far more powerful. (And although I’m glad it will never happen, it would be a great slogan for a social network site or a mobile operator.)

Why don’t copywriters stop making sense more often? The most obvious answer is that ad campaigns, unlike song lyrics, have to be developed and approved by lots of different people working together. Without consensus on the message (or ‘brand values’), the campaign would never get signed off, and the renegade surrealist ad creative would never get their work published or broadcast. In marketing, as in music and other art forms such as film, a lot of the things that happened in the 60s simply could not happen again. ‘Once there was a way to get back homeward…’

Tags: John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Revolution in the Head, The Beatles