Five metaphors for Brexit

Brexit is complicated: an unprecedented negotiation involving myriad intersecting political interests, treaties and organisations. Even those who are actually involved clearly don’t understand it all. So it’s no surprise that the rest of us look for ways to make it simpler.

Metaphors are ways of seeing. They help us understand what we don’t know in terms of what we do. However, that helping hand has a cost: metaphors make some things clearer, while obscuring others.

Because of this, relying on a particular metaphor might make certain outcomes more or less likely. So rival interests weaponise their metaphors, struggling to win framing contests and get their way. However, as with writing, if you overburden a metaphor, it will collapse under the weight.

In this piece, I look at five popular Brexit metaphors, how they might shape our thoughts and some we could use instead.

Brexit as… something easy

It seems a long time ago, but in 2016 some maintained that we could ‘have our cake and eat it’ in our relationship with the EU. That instantly made Brexit sound tasty, easy (‘a piece of cake’) and comfortingly traditional. It was the ideal appeal to the older, country-dwelling Brexiter – or Bake Off viewer.

Unfortunately, ‘cake’ (and, by extension, ‘cakeism’) quickly became a byword for fantastical thinking among British politicians. By the time party-pooper Donald Tusk admonished them, ‘Buy a cake, eat it, and see if it is still there on the plate,’ the metaphor had gone decidedly stale. (But isn’t it curious that while everyone loves cake, nobody likes a fudge?)

Around the same time, David Davis was breezily insisting that we could get a ‘quickie divorce’. However, once it became clear that we would actually be embroiled in endless to-and-fro about who’d get the Titanic DVD and see the kids on Saturdays, this ‘easy’ metaphor was also discreetly dumped.

Brexit as a journey

More fruitful is the idea of Brexit as a journey. Things aren’t working where we are, so we need to go somewhere else.

The parallel between development and motion runs so deep in our minds that we scarcely notice we’re using it. But whenever we talk about ‘going back’ to a previous situation, ‘moving on’ to something new or progressing ‘onward and upward’ (and many more), we’re seeing time, progress or events in terms of physical movement.

Even the fundamental notion of being ‘in’ or ‘out’ of the EU implies a location or container, while ‘leaving’ creates an illusory sense of distance. After all, we’re not really going anywhere; we’ll still be right here, just across the Channel.

So if Brexit is a journey, what does that imply? Our path might be laid down for us, or we might come to crossroads and have to choose the right way forward. Certain options might mean retracing our steps, or giving up ground. And we might need a map or guide to help plot our course.

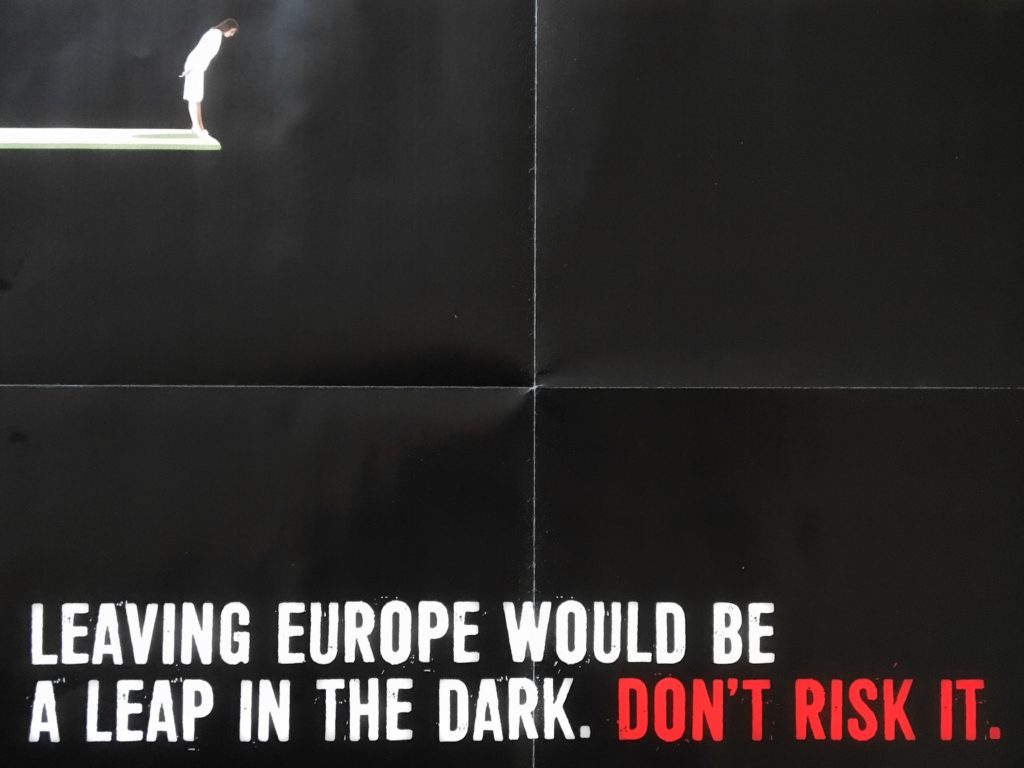

During the referendum campaign, Remain warned us that Brexit would be a ‘leap in the dark’. Don’t go down that road; stick to the straight and narrow. Unfortunately, that made staying in the EU sound staid and unadventurous, or like standing still.

Boris Johnson went further by comparing EU membership to a prison cell (a Soviet one, says Jeremy Hunt), and Brexit to sunlit meadows. As ever, his yearning to transcend physical constraints – usually by building some stupid bridge – reflects his fatal impatience with the detail. It’s ludicrous, but it appeals to our sense that we should move on, strive for more and strike out for pastures new. The grass is always greener, after all.

Motion brings momentum, which helps to keep the show on the road, even as the wheels come off. There’s no turning back now; we must keep calm and carry on. This also exploits the sunk costs fallacy: the sense that we’ve ‘come this far’ and ‘might as well’ finish Brexit now – even if it won’t actually do us any good.

Now negotiations have ‘reached an impasse’, which might imply that we can only ‘make headway’ through the dynamite option of no deal. As Brexiters’ total lack of a plan shows, it would have been better to choose our destination before we set off.

Brexit as a prize

The word ‘Brexit’ is genius because it turns an idea into an object. While Remain is a puny-sounding verb, simultaneously evoking both posthumous relics and unappetising leftovers, Brexit is a proper ‘thing’, with its own name and everything.

Nounifying Brexit turns it into something ‘out there’ that we must find. But what actually is it? Brexiters’ blind faith and crusading zeal suggests that it might be the Holy Grail, which will usher in a golden age once recovered.

This view also drives the ‘doing it wrong’ narrative of Jacob Rees-Mogg and Mervyn King. For these white knights, the goblet clutched by the prime minister is not the one true grail, but some treacherous chimera conjured by a warlock of Remain. We must redouble our search for the unicornical ‘Brexit prize’ – which, for some reason, nobody has yet caught sight of.

A prize is all upside and no downside, so this metaphor stretches credibility to breaking point, particularly this late in the day. The idea of a financial product, suggested by ‘Brexit dividend’, at least implies some cost or investment to obtain the bonus. But it’s still a lie.

Brexit as a battle

When Theresa May talks about getting a ‘good deal’, she doesn’t mean a mutually beneficial agreement with our friends, neighbours and trading partners of 40 years. She means a deal that’s good for us. In other words, winning.

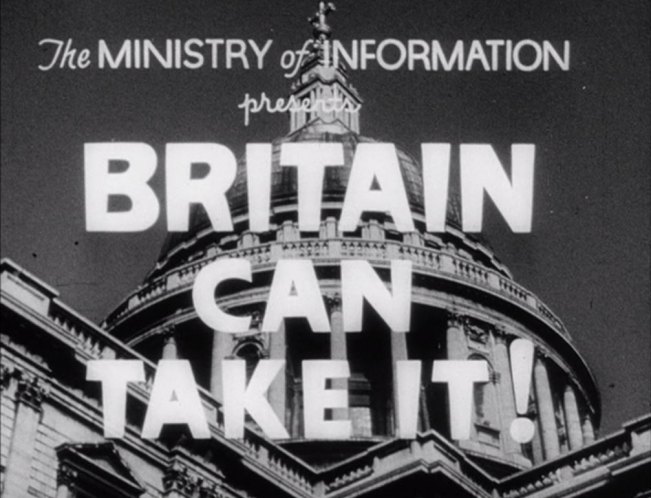

That plays to Leave voters, but it also reflects British nostalgia and exceptionalism. It seems we can’t (or won’t) abandon our second-hand sentimentality about the Second World War, as if we were living in Dad’s Army. ‘We’ got through the Blitz; we can get through this. Bring back the ration books. Britain can take it!

The martial tone is reinforced by the use of words like ‘campaign’, ‘taskforce’, ‘opening salvoes’, ‘stick to one’s guns’ and ‘shot across the bows’ – and, of course, Nigel Farage’s grotesquely insensitive ‘without a single bullet’. Later on, as victory began to slip away, we started hearing about ‘sabotage’, which makes Brexit sound like some daring undercover mission or vital engine of war.

The advantage of a war metaphor is that it casts anyone who demurs as a traitor. Questioning the actions of your elected representatives isn’t a democratic right, it’s a betrayal. It also helps reframe our departure from the EU as an act of foreign aggression, rather than a defeat we’re inflicting on ourselves.

Some aspects of our deal are ‘zero sum’, such as the single market (we’re either in or out) and money (we have it or we don’t). The key to transcending that narrow, tactical mindset is to focus on broader strategic goals. The EU wants to hold the line without any further desertions, while we need to appease our racists without blitzing our economy. Obviously, we won’t achieve those outcomes by treating our co-creators as the enemy.

Brexit as a game

The metaphor of Brexit as a game de-dramatises the negotiation, but trivialises its outcome. It supports Old Etonians’ idea of politics as a school debating contest – but unfortunately, they’re playing with people’s lives.

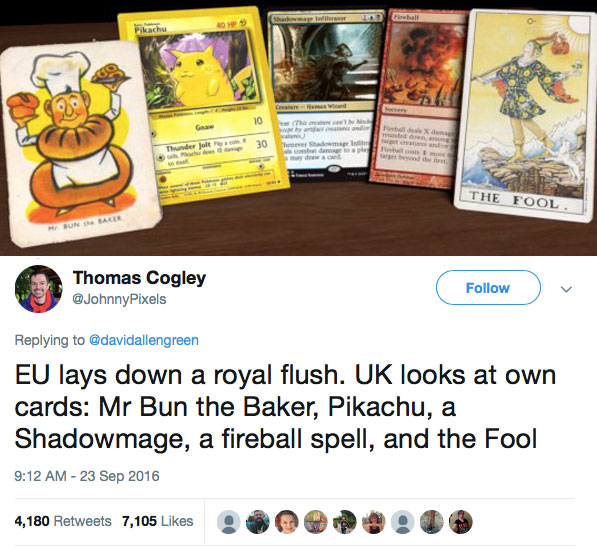

Originally, the negotiations were portrayed as a game of poker. During the 2017 election, we were told to give Theresa May a ‘strong hand’ – which we could do by electing more moderate Tories to dilute the madness. If this was poker, it was a nine-year-old’s made-up variant where May could draw another 10 cards while discarding none.

Obviously, May didn’t get her full house (of Parliament). Since then, we often hear of ‘showdowns’ with the EU, or that one or other side might be bluffing. In our case, our bluff is the threat of no deal, which is a bit like threatening to walk away and let your opponent take the pot.

As I write, Labour is edging towards support for a ‘people’s vote’. But no sooner had the word ‘remain’ left Keir Starmer’s mouth (thank you Keir) than rabid Brexiters were howling that Labour would take us ‘back to square one’.

Suddenly, we’d left the casino table for the lounge carpet, and a game of snakes and ladders. But ‘back to square one’ implies that progress has been made. If Brexit’s a board game, we’ve lost the dice, our siblings are crying in the bathroom and the dog’s chewing the box.

If not those, what?

Most of the metaphors I’ve discussed are pro-Brexit. If a second referendum comes, we’ll need to encourage former Leave voters to switch – not by patronising or browbeating them, but by offering some friendly suggestions in everyday language. Here are a few ideas.

If Brexit is a game, then clearly nobody can win it. So let’s play another one. A fresh vote isn’t ‘back to square one’, it’s ‘get out of jail free’, or a chance to play our joker.

If a friend was recklessly leaving a partner who was basically OK, perhaps after an argument, we’d encourage them to stick together. On the other hand, if they’d been manipulated and gaslighted the way Leave voters were by Brexiters, we’d implore them to break free.

If our friend was moving to a new house instead when their old one seemed fine, we’d ask whether it might be better just to stay put and redecorate. And if they were walking away from a cushy job to try and compete against their former employer, we’d query whether they really wanted to go through all that for such an uncertain reward.

We can all recall a time when we’d have acted differently if we’d known what we know now. If a friend had bought something that didn’t work as promised, or gone on a holiday that didn’t live up to the brochure, we’d tell them to go back for a refund. And if they’d taken a wrong turn, we’d advise them to get back on track, not keep blindly pushing on.

In my view, Remain has suffered from a consistent failure of imagination. We simply haven’t come up with the images and stories to support our case, while Brexiters have found plenty. If we want to win our own prizes, battles or games, we need some words that don’t sound like losing, standing still or giving up – and fast.

Tags: Boris Johnson, Brexit, Britain Can Take It, cake, cakeism, Crush the Saboteurs, Dad’s Army, David Davis, divorce, Donald Tusk, EU, European Union, framing contests, Great British Bake Off, holiday, Holy Grail, Jacob Rees-Mogg, Jeremy Hunt, metaphors, Michel Barnier, Mr Bun the Baker, poker, shadowmage, snakes and ladders, square one, The Fool, Theresa May