Remain’s seven big marketing mistakes

If recent events prove anything, it’s that if you ask a stupid question, you’ll get a stupid answer. But they also show that if you do call a referendum, and your success depends on millions of people agreeing with you, you need a decent marketing plan in place from the start. Here are seven things I think Remain should have done differently.

Weak positioning

Brexit is basically retrogressive, promising to restore something ‘lost’ rather than build anything new. And yet its campaign still managed to strike a positive note, with the genius slogan ‘Take Back Control’ and its insistence on how wonderful post-EU life would be.

Remain seemed positive, at least on the face of it. After all, its slogan was ‘Stronger In’, not ‘Weaker Out’. But ‘Stronger In’ still refers mainly to the UK, and only indirectly to the EU. Implicitly, it places the UK at the centre of everything. That prematurely conceded a key point about the value of the EU and our place in it, allowing debate to play out on Brexit’s home turf.

No positive benefits

By focusing attention on the UK, Remain gave up its chance to tell us about the ‘product’ it was ‘selling’. A sense of why the EU was a good thing, and we should want to be part of it, was nowhere to be found. Instead of being given positive reasons to stay in, all we got was negative reasons not to leave.  The lack of clear benefits left Remain looking hollow and lacklustre. Choosing Remain, it seemed, merely meant settling for the status quo. In contrast, Brexit looked dynamic and ambitious. The referendum thus became a choice between acting and gaining something on one hand, and doing nothing for no net gain on the other.

The lack of clear benefits left Remain looking hollow and lacklustre. Choosing Remain, it seemed, merely meant settling for the status quo. In contrast, Brexit looked dynamic and ambitious. The referendum thus became a choice between acting and gaining something on one hand, and doing nothing for no net gain on the other.

Of course, there’s little point in acting if your actions are misguided, impulsive, self-destructive or pointlessly insolent. But Brexit voters clearly felt, rightly or wrongly, that they had nothing to lose. Remain had to fight that by showing them they still had a lot to gain.

Too much knocking copy

Slagging off the competition is a big risk. You put the focus on your rival, guaranteeing they stay ‘front of mind’ for your audience, while simultaneously tainting yourself with negativity. If people aren’t listening carefully, all they’ll take away is a sense of you being a moaner, a bore or a killjoy – plus, possibly, a desire to disobey you, or side with the underdog.

As Project Fear let fly its fusillade of threats, scare-stats and expert warnings, it seemed completely unaware that it was coming across like a finger-wagging Victorian parent. Remain carried on doing the same thing but expecting a different result – the classic definition of insanity. Ultimately, that allowed Michael Gove to outflank it with his infamous retort that ‘people in this country have had enough of experts.’

Losing control of the facts

Gove’s ‘experts’ barb illustrates that you can lose a factual argument even when the facts are apparently on your side. David Cameron and his ministers had far greater reserves of statesmanlike authority to draw on than Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage, yet they ended up on the defensive. Why?

As Will Davies argues, ‘In place of facts, we now live in a world of data… a dizzying array of numbers is produced by default, to be mined, visualised, analysed and interpreted however we wish.’ We’ve moved into the age of post-truth politics, where big decisions are built on the flimsiest foundations. Needless to say, social media hasn’t helped.

Perhaps the most mendacious of Brexit’s claims was its infamous ‘£350m a week’. Remain repeatedly attacked it as an outright falsehood, yet it was still standing on the day of the poll; if anything, it seemed to have gathered strength. Only now, as Brexit’s leaders back away from it, is it beginning to crumble.  A lie is a lie. But it can still have weight if it feels plausible (truthiness), or if people are willing to base decisions on it (satisficing). If a lie is working for people, and they’ve actively taken it up, calling it out as false may not be enough.

A lie is a lie. But it can still have weight if it feels plausible (truthiness), or if people are willing to base decisions on it (satisficing). If a lie is working for people, and they’ve actively taken it up, calling it out as false may not be enough.

Instead of simply saying ‘that’s not true’, a better response to the ‘£350m’ claim would have been to supplant it with a different fact, turn it into a positive (‘look what we get for our money’) or place it in a different context.

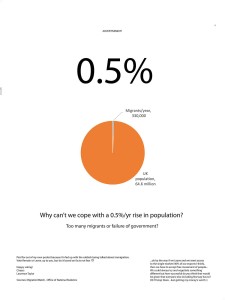

A great example of this last tactic was shared by Bob Mortimer (of all people) in the last days of the campaign (see below), showing the UK’s EU contribution as a tiny 0.37% of its annual spending. Why wasn’t it a central part of Remain’s messaging?

What the UK spends its money on. Puts EU spend in proper context pic.twitter.com/F9QpPPMDFs

— bob mortimer (@RealBobMortimer) June 22, 2016

In the end, it was down Laurence Taylor, a private citizen, to deploy the same idea in his self-financed full-page ad in Metro, this time focusing on migration.

No storytelling

As Jeanette Winterson pleads, ‘If we’re living in a post-facts world – let’s have better stories.’

Stories have the power to convey complex ideas about human behaviour and psychology in a simple way. By showing us how we are, and why we do the things we do, they can help us make better decisions.

Once stories have been told, the ideas they contain can be evoked time and again with only the briefest of phrases (‘cry wolf’, ‘sour grapes’). And that’s a gift to the marketer selling a subtle proposition.  Faced with Brexit’s xenophobia, Remain had to offer something with more substance than mere gainsaying, and story could have been it. European history is hardly short of compelling narratives pointing to the need for harmony.

Faced with Brexit’s xenophobia, Remain had to offer something with more substance than mere gainsaying, and story could have been it. European history is hardly short of compelling narratives pointing to the need for harmony.  Or, since many voters clearly didn’t know what they were opting out of (see image above), Remain could have simply told the story of the EU, which would have allowed it to show why the EU exists, what it does, how it helps and why we should be part of it.

Or, since many voters clearly didn’t know what they were opting out of (see image above), Remain could have simply told the story of the EU, which would have allowed it to show why the EU exists, what it does, how it helps and why we should be part of it.

Wrong tone of voice

Vote Leave shamelessly rode the coattails of Nigel Farage’s populist prejudices. But they also benefited from his chirpy personality, particularly in combination with Boris Johnson’s more languid insouciance.

In contrast, Remain’s default tone was relentlessly dour and threatening, to the point where not even the most committed Remainers could really argue that its stuff commanded more interest than Brexit’s.

Tonally, the effect was like an Orange Tango ad up against a fire-safety campaign. In this case, the devil really did have all the best tunes.

Ignoring the creatives

As Claire Beale writes in Campaign, the Remain campaign foundered partly for want of a ‘big debate-defining advertising image that voters would carry with them to the polling booth’. Despite meeting loads of big agencies and seeing some (apparently) top-notch creative work, Remain couldn’t commit, leaving a vacuum for Leave EU to fill with their deplorable ‘Breaking Point’ poster.

If that’s true, it’s one of the saddest things about the whole affair. Remain were given the creative ammunition they needed, but left it on the meeting-room table, killed by committee. But then, discord and disagreement have been the theme all along – and it only seems to be getting worse.

Comments (2)

Comments are closed.

Excellent assessment.

Excellent assessment, thanks Tom. One of the best arguments I saw was on the eve of the vote, by Sheila Hancock on the Jeremy Paxman programme. It made a massive difference to the ‘unsures’ present, and would have been great to see something like that used on a wider scale, but too little too late.