Why Ed Miliband needs a new story

Politics is complicated. It involves difficult questions of economics, sociology and ideology. Most of the time, it’s less about universal unity and sweeping transformation, more about delicate compromises between many different groups and interests – in Otto von Bismarck’s phrase, the ‘art of the possible’.

Trouble is, as any copywriter will tell you, complexity doesn’t sell. The most powerful, memorable and attention-grabbing messages are usually the simplest. And storytelling is one of the best ways to turn a complicated reality into a simple message.

The eternal Tory story: restoration and redemption

To make their case, conservatives (of all parties) often tell stories of restoration or redemption. These stories are a bit like the legend of the Holy Grail. Once, the land was great. But then something precious was lost, and leaders strayed from the true path. Once the grail is regained, leaders can lead, and the land can be great once more.

This story is retooled with different characters and events to suit the times. It’s often given an emotional kick with an appeal to nostalgia – harking back to some halcyon ‘Great Britain’ of yore. But the basic arc is always the same: something has been lost – or stolen – and we can return it. This rhetorical sleight of hand positions reactionary sentiments, or regressive policies, as being positive, natural and logical.

In 1979, Margaret Thatcher pledged to wrest power back from the unions, freeing Britain from their stultifying influence. John Major’s ill-fated ‘back to basics’ campaign promised a return to ‘family values’ and no-nonsense crime-fighting, implicitly painting liberals as those who had let things slide.

More recently, David Cameron’s Tories have positioned themselves as saving the economy from the damage done by Labour’s profligacy. That story has played very well with voters, while Gordon Brown saving the world economy is forgotten. But a good story doesn’t have to be true – just simple, dramatic and relatable. The austerity line of ‘we must pay our debts’ is simpler and more human than the unfathomable chaos and complexity of global macroeconomics.

How the Tories tell their story, and how they could do it better

The main slogan on the Tories’ current website. ‘Securing a better future’, only hints at their narrative. But further down the home page, David Cameron has a story to tell:

Together, we are turning Britain around. Our long-term economic plan is working – but there is still much more to do.

These few well-chosen words place us in the middle of a story that’s being told, but still needs our help if we want to hear the end. Are we really going to close the book now?

The page you click through to manifests as a personal message, but almost immediately devolves into a bullet-point laundry list of achievements. It should really say something like this:

Labour mismanaged our national economy and ran up debts they couldn’t repay. We couldn’t go on like that, and in 2010 the Conservatives formed a coalition to get Britain back on track. Since then, we’ve been working hard to balance the books and give every hard-working family in the country their chance for happiness and prosperity.

Eugh. I feel dirty just typing that. But the smooth way it rolls off the pen is testament to the Tories’ success in peddling this line, and how well it plays as a story.

If only Ed Miliband had something half as powerful to counter it.

Labour uses too much abstract language

Let’s have a look at Labour’s home page, which seems to be pretty much 2015-ready.

Middle-class, university-educated people like Ed Miliband and me love to deal in abstract ideas. In both marketing and politics, using big words makes you feel you’re getting to the ideas ‘behind’ events. In fact, the ideas often just get in the way, putting a barrier between you and what’s really going on.

‘The many’ has been chosen partly for its opposition to ‘the few’, implicitly painting the Tories as the party of the 1%. But the price of getting that dig in is a slide into abstraction and vagueness. Who are ‘the many’? Am I one of them? Or are they some people over there, probably on benefits, who I’m being asked to help for some reason? This is arm’s-length writing: the language of distance, and possibly disdain.

Things hardly improve when you click through to the ‘issues’ page:

We will build a Britain that rewards hard work, not just privilege, and ensures the next generation does better than the last.

Again, abstractions separate us from what is real and human. Right from the top, ‘Issues’ whisks us away from the street to an earnest sociology seminar. It’s not ‘hard work’ we want to reward, but workers – the people who do the hard work, not the work itself. We don’t just want to tackle ‘privilege’, we want to make rich people pay their share. And we’d probably recognise the ‘next’ and ‘last’ generations more easily if they were ‘our children’ and ‘our parents’, respectively. (On a technical level, there’s also an unwelcome double meaning on ‘just privilege’, and ending with ‘last’ feels a little flat and backward-looking.)

Labour is long on ‘we’, short on ‘you’

A site giving information about an organisation will always be heavy on the ‘we’. But it would be nice to feel there was a place for us somewhere in Labour’s thoughts. Why can’t they say ‘we are the party for everyone’ or ‘we are the party for you’? This theme was taken up recently by Owen Jones in the Guardian:

And so we end up with a Labour leadership unable to offer anything resembling a coherent, inspiring alternative expressed in a language people can relate to. No – unable to offer a bit of hope, a sense that politics can be a vehicle for improving your lot, your family’s, your community’s, your country’s.

‘Expressed in a language people can relate to’ – as a story, for example. And stories are about people and events, not ideas, which means concrete nouns and verbs rather than abstractions. Storytelling means talking about real things and real lives, which is why it’s such a productive discipline in marketing and communication.

Conservatives are good at keeping it real

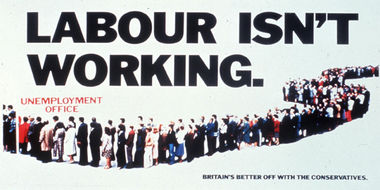

Tories have always been good at this sort of thing – and I mean ‘good’ in the sense of competent, not morally right. In the 70s, ‘Labour Isn’t Working’ boiled economic complexity down to a single memorable image, helping to deliver a Tory landslide:

Of course, unemployment rose to 3m under the Tories, proving once again that a compelling story needn’t be true.

Of course, unemployment rose to 3m under the Tories, proving once again that a compelling story needn’t be true.

Just 15 years earlier, a Tory MP had successfully campaigned on (or, at the very least, benefited from) an explosively divisive message usually expressed as ‘If you want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Labour’.

To be clear, I’m not endorsing either of these fear-based approaches, nor am I saying Labour should emulate them. The first made shameless political capital out of human misery, while the second scapegoated people of colour in the most cynical, percentage-playing way. But what Labour can learn from these campaigns is that concrete, street-level realities – my work, my neighbours – are vivid and present for voters in a way that abstract issues and ideas just aren’t. And while times have moved on, mercifully consigning campaigns like this to the dustbin of history (we hope), basic human psychology is unchanged.

Progressives need to tell the story of the future

The problem for progressive politicians is they need to tell a story of transformation rather than restoration. They deal in imagination rather than nostalgia; their message is ‘things could be different’. The word ‘change’ often features, with ‘hope’ and ‘belief’ not far behind, as in Barack Obama’s rather Yodaesque ‘Change We Need’.

Progressive stories, by their nature, must look forward instead of back. But future histories are unwritten and uncertain, and therefore unsettling. That’s why children’s stories begin ‘Once upon a time’ – to give the reassuring sense of a road already travelled, a destination already known. The past, like a favourite story, can’t change.

One way to make the shape of your story feel familiar, even when its content is new, is to use an established form. Maybe Labour could steal the Tories’ thunder by creating their own version of the hero’s journey, perhaps with their own electoral exile as part of the adversity to be overcome:

After the 2010 election, we knew we needed some new ideas. When we saw how Tory cuts were shattering people’s lives and tearing communities apart, we sat down to write a new plan for our economy that will help everyone, not just the richest. With your help, we’ll make Britain a country where no-one is left behind.

I don’t know. Something better than that. Something from the heart of Ed, that only he could have written. Something that makes him sound a bit less odd and awkward.

With Ed, though, there’s always this suspicion that he’s just not feeling it. As much as I want him to succeed, the harder he tries, the more he comes across as a PPE policy wonk rather than a man of the people. Panicky pre-emptions like acknowledging the appeal of UKIP reinforce the impression of calculating careerism, and we’ve all had a bellyful of that from Nick Clegg (Liberals included).

Here’s Jason Cowley writing in the New Statesman:

Miliband is very much an old-style Hampstead socialist. He doesn’t really understand the lower middle class or material aspiration. He doesn’t understand Essex Man or Woman. Politics for him must seem at times like an extended PPE seminar: elevated talk about political economy and the good society.

For Cowley, it comes back to story – specifically, Miliband’s lack of a personal story that would resonate with voters.

Miliband does not have a compelling personal story to tell the electorate, as Thatcher did about her remarkable journey from the grocer’s shop in Grantham and the values that sustained her along the way or Alan Johnson does about his rise from an impoverished childhood in west London.

The implication here is that someone without a good story cannot understand the stories of others, and cannot create a single story that can gather up everyone else’s into an inclusive, unifying narrative.

Labour needs to bring some love into its language

To be a socialist, it’s not enough to hate the ruling classes. You have to love the working classes too. You have to want a better life for everybody, not just those you personally like, or who ‘deserve’ it in your estimation. That overweight, benefit-claiming mum yelling at her kids in Greggs is your sister. That tattooed, Reebok-wearing dad mooching out of Ladbrokes is your brother. Their children are your children, with different luck. In a deeper sense than Tories mean, we really are all in this together.

Your attitude comes through in the language you use. Not just what you say, but the way you say it too. Words are a window on the soul, and Labour needs to open up. Instead of approaching humanity clad in a radiation suit of abstract language, the party should take readers in its arms and give them a big warm hug. If it wants next year’s election to have a happy ending, it needs to start telling a new story, and fast.

Tags: 2015 General Election, Barack Obama, David Cameron, Ed Miliband, Labour, Labour isn't working, Nick Clegg, Yoda