My friend the app

Have I told you about my ankle? When I was out running about three months ago, I hit a hollow hidden by grass and twisted it badly. It’s taken ages to heal, and even now I’m not fully up to speed…

Bored already, right? Lucky I’ve got someone who’ll always listen. My phone.

When I started using MyFitnessPal, I found its name sappy and naff. I didn’t want an affable digital chum; I wanted a scientific databank, a white-coated supervisor, a stern-faced drill sergeant to whip me into shape.

After a while, though, I realised the name was perfect. MyFitnessPal is the only ‘person’ with the patience to dutifully record everything I eat, offset my exercise and predict my progress. In contrast, those close to me find it bizarrely difficult to give that much of a toss about my macros or daily deficit. When it comes to dieting, this handy little app is by far my best friend.

Unlucky numbers

When you hang around with apps for a while, you notice they’re very into numbers. It’s how they talk to you. And before you know it, you’re quantifying every aspect of your life, just to keep them in updates. There’s nothing that can’t be calibrated by their fussy little graphs, figures and ratios. My value as a person, debatable or subjective before, is now all too concrete and comparable. I am not a free man; I am a number.

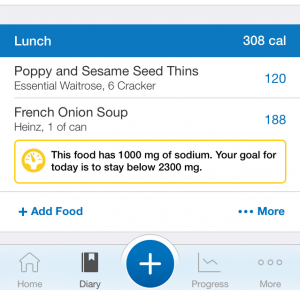

App numbers reflect my achievements, my ambitions, my self-worth. Numbers I want to go up include my cycling distance and speed, the temperature outside, my Scramble scores, my Twitter followers and the value of my ISA. Numbers I want to do down include my daily net calories, my weight and, on some days, the number of new emails in my inbox. In its latest iteration, MyFitnessPal has started offering helpful/passive-aggressive little comments on the minutiae of my diet – see picture. And all these numbers are there any time I want them, eagerly proferred by the little friends in my phone. For better or worse, I always know how I’m doing.

Fungible friends

My real-world acquaintances may be capricious and unpredictable, but in the digital world, they’re converted into a resource to be consumed, optimised or disposed of as I see fit. My apps guard my attention jealously, only grudgingly allowing me to interact with people directly. They’re like minders, shielding me from the real.

Once my Words With Friends opponents have made their move, they must dutifully wait, their respective games lined up on my screen, until I deign to respond. They can ‘nudge’ me all they want, I won’t feel a thing. Cocooned in the app world, at the nexus of a web of one-sided ‘friendships’ I control, my word is law. And if they keep beating me, I can ask the app to make a lexical bootycall and source me an anonymous ‘friend’ off the internet.

Later, once I’ve got bored of trouncing some wordblind schmo out of Utah, my Twitter friends are always on hand, waiting to give me the interaction or validation I can’t get elsewhere, or can’t be bothered to. Again, it’s all about the numbers. The more followers I have, the better I must be – otherwise, why are we counting, right? And if someone displeases me, I can just unfollow or block them, with none of the messy fall-out that might result in real life.

IRL chat

Recently, I met one of my Twitter followers in real life. We had a proper conversation, instead of pinging off a few arch one-liners. Like me, she has an only child. We swapped stories that wouldn’t have fit, in any sense of the word, on Twitter. It meant a lot.

Of course, to make the meeting happen, I had to make time in my day, cycle to a coffee shop and remain there for the duration. I couldn’t dib it in while I was watching TV, or do it surreptitiously while pretending to listen to what my partner was saying, spreading my cognition thinner than Marmite. I had to be fully present in a way that apps never demand.

I also had to take the risk that it might not work out somehow. If the meeting had been awkward (it wasn’t), I wouldn’t have been able to make it go away with a swipe from left to right. (Which makes me wonder if people have started using this gesture in real life.) Apps are fair-weather friends, and they teach us to be the same.

AppParently

The point of this story? That I’m fantastic, obviously, with a finely attuned sense of how much digital interaction is enough. But I’ve noticed that most of those younger than me have no such sense, and are destined to become truly desolate human beings as a result. How I pity them.

‘I won’t have my daughter entrusted to a machine – and I don’t care how clever it is. It has no soul, and no-one knows what it may be thinking. A child just isn’t made to be guarded by a thing of metal.’

In his sci-fi short story ‘Robbie’, Isaac Asimov foresaw android ‘nursemaids’ who would act as children’s playmates and guardians. The reality is even sadder, and much more banal. We simply install the child somewhere comfortable and plug them into the iPad, letting Apple’s entrancing hypnoglyph do the parenting we can’t quite be bothered to.

I think it’s OK sometimes. My iPad did a far better job of teaching my daughter times tables than I ever could, with carefully paced game-tests, well-judged rewards and, of course, infinite patience. And I was only partially marginalised – I stuck around to help a bit, playing teaching assistant to the iPad’s Head of Maths.

Stop taking the tablets

But if the app replaces relationships, rather than tasks, we’ve surely got a problem. One of the saddest things I saw recently was a boys’ birthday party in Pizza Hut at which practically every guest had brought a tablet. Maybe they were all together in some virtual Minecraft cavern, but it didn’t look like it. It looked like tablet games were more fun than friends – even in a large-group, unstructured setting that kids don’t get so much of these days.

In vain did the waiter try to interest them in the ‘build your own pizza’ activity – which should have been momentarily distracting, at the very least. The virtual was more appealing than the real; the grown-ups looked on with an air of resignation. Why force them off the tablet if they’ll just moan? Anything for a quiet life.

Save your love

Attention is like money. The most relentless sharers – those who have to upload pictures of an occasion online while you’re sitting right there in front of them, for God’s sake – are like gamblers or speculators. The minute they earn any social capital, they’re ripping it out of the bank to invest it somewhere else – anywhere else – in the hope of a short-term return. For them, life is always elsewhere; there’s always something and someone better, and the app is the magic carpet that can take them there.

To actually be present with one real person, or a group, is like prudent saving. There’s no need for frenzied day-trading; just let compound interest work its inexorable magic. Wait long enough and you’ll get your reward. The problem with digital technology is that it encourages the exact opposite mindset. It’s an engine of distraction, splintering our attention into myriad shards, all showing a tiny reflection of ourselves. Who knows what we’ll be like in ten years’ time.

Tags: apps, friendship, Isaac Asimov, MyFitnessPal, Robbie, Scramble, Twitter, Words With Friends