What is brand storytelling, anyway?

For copywriters, the need for storytelling is as obvious as it is essential. Meat-and-potatoes assignments like case studies, company profiles and press releases all naturally frame themselves as stories. On a more creative level, narrative gives life and form to many broadcast and long-copy ads, or livens up ‘dry’ publications such as annual reports or slideshow presentations.

When we get into ‘brand storytelling’, though, things get complicated. Sometimes, it seems to be about writing the things I just mentioned, but with the aim of promoting a brand rather than a product. In this area, it seems it can also overlap with brand values, company vision and sometimes tone of voice. Some brand storytelling is meta-content that spreads the word about the process of creating or refreshing a brand, like Starbucks’ So, Who is the Siren?.

In the digital realm, ‘brand storytelling’ seems to be defined differently, and is more often positioned as an innovation. It’s closely related to content marketing, the idea of ‘brands as publishers’ and stories told by customers (i.e. user-generated content).

Then we have ‘brand story’. Sometimes, this is an actual story, perhaps based on company history, that gets published in various media. At other times it’s closer to values or mission – an underlying theme, not necessarily narrative, that unites different strands of marketing. And sometimes it’s more like an ethos or an approach – a way of thinking about a brand through the lens of narrative.

I’m honestly confused by all this, so I was pleased to see this recent article in Marketing Week, which looks at how some top brands ‘do’ brand storytelling. Reading it quickly confirmed that the whole idea of brand storytelling is very much up for grabs. As the piece admits, ‘storytelling is a broad concept that means different things to different marketers’. In this respect, it’s rather like its cousin ‘engagement’ – and offers the same potential to hypnotise marketers and bamboozle their clients. (Perhaps that’s why nobody shortens ‘brand storytelling’ to ‘BS’.)

Marketers may not know exactly what brand storytelling is, but they are sure it’s very important. It’s constantly touted as the Next Big Thing (after content marketing, of course) and was far and away the most requested topic when we began planning the PCN Conference.

Brand storytelling as media spend

The Marketing Week article quotes a OnePoll study, commissioned by story-centric agency Aesop, into top brands’ storytelling. Consumers were asked whether brands ‘have a clear sense of purpose’ and ‘create their own world’, and whether people were ‘intrigued to see what they’ll do next’. Their responses were used to rank brands into a top 100.

You can see the full list at the original article, but here’s the top 10 (descending): Apple, Cadbury, Walkers, Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, M&S, Kellogg’s, Heinz, Fairy, IKEA.

A cynic might observe that brand storytelling seems strongly correlated with big media spend, begging the question of whether the phenomenon being termed ‘storytelling’ is really all that different from simple brand recognition.

For example, if we review the top-spending advertisers in 2011, we see Apple at 54, Cadbury at 59, Coke at 24, McDonald’s at 20, M&S at 13, Kellogg’s at 10 and P&G (owners of Fairy) in the top spot. Only Walkers (owned by PepsiCo), Heinz and IKEA don’t appear in the top 100.

No rogue challenger brands have achieved top billing on the strength of their stories alone, suggesting that telling a story effectively means having the media muscle to drive your message home. (Although, to be fair, they might not have been included in the survey at all.)

Brand storytelling as interest gauge

The OnePoll survey also ranks sectors for their storytelling. The top ten is as follows: retail; food and soft drinks; FMCGs; restaurants; telecoms/tech; airlines; alcohol; automotive; financial services; utilities.

This is adduced as evidence of banks and utilities being bad at storytelling, and Barclays is cited as a financial services brand trying to do better. But to me, this seems like a very roundabout way of arriving at a self-evident truth: some brands, and some products, are just more appealing than others.

If I recast the list in terms of people’s interests, you’ll see what I mean: shopping, eating, looking good, eating out, gadgets, holidays, drinking, cars, sorting out money, paying bills. I’m not sure banks and utilities could capture consumers’ hearts if they had the best stories in the world – they just don’t command enough positive emotion.

Brand storytelling as self-congratulation

For branding advocates, Apple’s presence at number one is a problem. As Bob Hoffman has noted, Apple built its stellar success on a near-total avoidance of ‘branding’, not to mention social media. It’s the most successful old-school advertiser in the world.

How to square the circle? Here’s a quote from the Marketing Week piece:

Ed Woodcock, strategy director and co-founder of Aesop… argues that Apple’s top ranking is the result of its almost evangelical commitment to creating technology that improves people’s lives and the clarity with which it tells that story.

No argument with the evangelism. But I don’t think Apple’s success has much to do with the ‘clarity with which it tells that story’. In fact, I’m not sure what ‘that story’ is – unless the term is so broad that it encompasses product design, user experience and the whole of marketing.

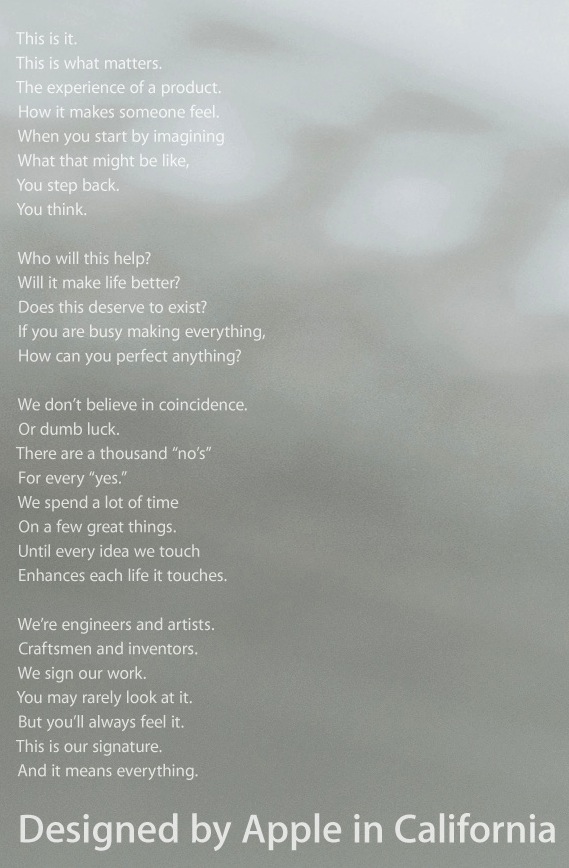

“[Apple’s] sense of mission manifests itself in everything it does: from the design of its products and stores to the simplicity of its advertising,” [Ed] says. Apple is currently running a campaign using long copy to explain the story behind its products.

Fair enough, but is ‘sense of mission’ the same as story? The ‘design of [Apple’s] products’ seems a long way from brand storytelling, and, as I’ve argued, the ‘simplicity of its advertising’ goes directly against it.

Fair enough, but is ‘sense of mission’ the same as story? The ‘design of [Apple’s] products’ seems a long way from brand storytelling, and, as I’ve argued, the ‘simplicity of its advertising’ goes directly against it.

Whatever consumers love about Apple, I don’t think it’s their story.

That’s not to say there are no stories behind Apple. There’s one on every page of Walter Isaacson’s Jobs biography. But Apple has never tried to bind them to its brand or products. When Apple does marketing, nothing gets between the consumer and the experience, not even words. All the creativity, values and humanity of Apple the company are concentrated and subsumed in an iconic, ultra-focused product that practically sells itself.

Until this year, when Apple deigned to create its first ‘brand story’ ads (apart from ‘Think Different’, maybe) – see image excerpt, right. But the ads don’t actually tell a story. They’re more a self-centred meditation on Apple’s approach to designing products. If this is ‘storytelling’, all it achieved was to interpose a new and completely needless voice between the consumer and the product. (For a full discussion, read Nick Asbury’s brilliant analysis.)

Brand storytelling as aspiration

With Apple, marketers foist the role of ‘storyteller’ on the brand. At other times, they arrogate it for themselves, not always convincingly. In many cases, one suspects that ‘story’ is a hipster label stuck on to traditional marketing to sex it up.

For an example, check out this tweet from agency True and Good:

Calling it a story doesn’t mean it is one… @waitrose #copywriting #storytelling #brandstrategy #creativity pic.twitter.com/tx5hKBiReM

— True & Good (@TrueAndGood) July 18, 2013

As they rightly point out, the headline writes a cheque that the body can’t cash. There’s no development, drama or dénouement. It’s a mood-board sentiment bolted onto a product description.

That’s not because you can’t tell a great story in such a small space – just have a look on Twitter. The point is that when push comes to shove, irrelevant story will always be pushed out by actual benefits.

We don’t give a toss about Heston’s passion for the movies. We just want to know if his ice cream tastes any good. If there really was a story uniting those two things, it would be great to hear it – but the attempt to cover two bases at once fatally compromises both.

Brand storytelling as smoke and mirrors

The poster child for brand storytelling is Coca-Cola, which launched its ‘Content 2020’ initiative a couple of years ago. This move electrified content-marketing circles, generating breathless articles saying that the brand was ‘betting the farm on content marketing’.

In fact, Coke has by no means abandoned traditional advertising, and the cost of the 44-person team assigned to Content 2020 could probably be accounted for by a rounding error in its global TV budget. It’s hardly gambling anything – apart from its reputation, perhaps.

The more I try to find out about this programme, the stronger my sense of emperor’s new clothes about it. The whole thing is clouded, pehaps deliberately, in an almost perverse mysticism. Can there ever have been so much baroque justification for the process of writing stuff and putting it online? Watch the video below – with its ‘brand stories’, ‘content excellence’, ‘provoking conversations’ and ‘liquid and linked ideas’ – and see if you agree.

The supreme irony, of course, is how little story there is. Beneath the cute illustrations and ‘chapters’ it’s actually the mother of all PowerPoint presentations.

If you stuck with it (and this is only part one), you now know all about the shift from ‘one-way storytelling’ to ‘dynamic storytelling’ – which is of course

the development of incremental elements of a brand idea that get dispersed systematically across multiple channels of conversation for the purposes of creating a unified and co-ordinated brand experience.

Got that? Practise saying it with a straight face and drop it into your next client meeting. Oh, and make sure you’re up on the distinction between ‘serial storytelling’, ‘multi-faceted storytelling’, ‘spreadable storytelling’, ‘immersion and discovery storytelling’ and ‘engagement through storytelling’ too.

What actually happens, as far as I can tell, is that Coke commissions some magazine-type articles about chilli peppers or German football and posts them under its new brand of ‘Coca-Cola Journey™’. People then share and comment on them – or don’t, in the case of those two pieces – and people from Coke respond. So, basically, it’s a sporadically off-topic company blog.

Do people really want to get their news stories from brands like Coke? I suppose they might, if the alternative is a newspaper site behind a paywall. But I still question the use of the term ‘storytelling’ – for me, this is content marketing, pure and simple. The idea of ‘story’ is merely being enlisted to give the enterprise a human resonance it doesn’t really have.

What’s the story?

I’m not saying that brand storytelling is rubbish. Aesop’s site has many good examples of the discipline, such as its fine work for Glenlivet, drawing on the brand’s rich history. My point is that defining the term ‘brand storytelling’ too ambitiously, or applying it too widely, makes something basic and elemental sound like a shiny digital novelty or an ineffable mystery. And that may not help those who actually have stories to tell.

Tags: Aesop, Apple, Barclays, brand storytelling, Branding, Coca-Cola, Content 2020, Glenlivet, Nick Asbury, story, storytelling, Think Different, True and Good, Waitrose