Plain English Patrol 4

Having been excoriated so harshly for it a few months back, I’ve been trying to stay off the pedantry. But it’s like being an alcoholic. You take one wrong turn, see an ad on a bus shelter and suddenly the disease is back in control.

I’ve been criticised, probably rightly, for having a go at inconsequential bits of copy, or blaming the writer for what could have been the client’s call. But I really don’t think either of those applies in this case. We’re talking about a high-profile campaign, for an international brand, created by one of the most highly regarded agencies in London.

Disastrophe

The target in the Patrol’s sights is the current poster campaign for Stella Artois, which has been rolling out through 2012. By the brand’s own standards, it’s a fairly middle-of-the-road affair, featuring white backgrounds, simple product shots and relatively traditional slogans on the theme of heritage and history (although it’s ostensibly united with the ‘She is a thing of beauty’ theme). Needless to say, it’s the slogans that concern us here.

Let’s start with this:

Master Brewers required.

600 years experience needed.

The problem with this is the ‘600 years experience’. No, it’s not the question mark over whether Stella has actually been brewed for 600 years, which others have raised. And it’s not beginning a sentence with a numeral – I’m letting that go since this is ‘just’ an ad. The real issue, although almost nobody seems to observe this rule any more, is that ‘years’ needs an apostrophe: ‘600 years’ experience’.

The reason for this is that the experience ‘belongs to’ the 600 years. Another way to put it would be ‘the experience of 600 years’. When this is condensed into ‘600 years’ experience’, the apostrophe expresses this sense of possession. (Here’s a post that backs me up.)

Another way to express it would be ‘600 years of experience’, but such a construction would only ever really be written, not spoken aloud, and we’re working in a conversational tone of voice here. But we still need the apostrophe, or we’re just jamming two nouns together without clarifying how they relate to each other.

Changing the subject

Now for another example – yes, from the same campaign.

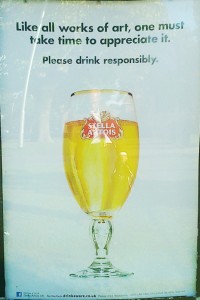

Like all works of art, one must take time to appreciate it.

(Apologies for mobile-phone photo.) Here, the issue is a confusion between subject and object caused by the subordinate clause being placed at the start of the sentence.

The subject of the main clause is not ‘it’ (Stella) but ‘one’ (the Stella drinker), so the subclause ‘like all works of art’ refers to ‘one’. The sense of the sentence is therefore ‘Because you’re like all works of art, you must take time to appreciate Stella’, which I’m fairly sure was not the intended meaning.

The line would have been better (if still technically wrong) the other way round…

One must take time to appreciate it, like all works of art.

…because that would have put the subclause nearer to ‘it’, helping to make it stick to the object rather than the subject. Aesthetically, though, that would be putting the cart before the horse by leading with the punchline.

With just a little tweak, the whole thing could have made perfect sense:

As with all works of art, one must take time to appreciate it.

Alternatively, if we wanted to keep ‘like all works of art’, we could go with:

Like all works of art, it takes time to appreciate.

But why not make the reader think a little, save some words and end on a stressed syllable (like Giles Coren always does)?

It takes time to appreciate art.

Up the bracket

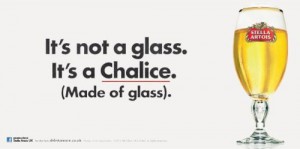

Let’s have one more before they close. Have a look at this poster.

It’s not a glass.

It’s a Chalice.

(Made of glass).

I wonder how many drinkers of ‘wifebeater’ know what the word ‘chalice’ means? Leaving that burning question aside, there’s no way the word can have a capital C. It’s not a proper noun (unless we infer that it’s short for ‘Stella Artois Chalice’, maybe) and it doesn’t begin the sentence. But let’s be charitable and put it down, along with the red underlining, to graphical emphasis – even if italics might have been more orthodox, brand-appropriate and visually attractive.

No such indulgence can be extended to the punctuation in the last line. In UK English, the only time you can have a full stop outside brackets is when the brackets enclose a subclause within the sentence that’s terminated by the full stop (like this). Since the previous sentence (‘It’s a Chalice’) has already ended with a full stop, ‘Made of glass’ can’t be a subclause of it.

That leaves ‘Made of glass’ as a standalone sentence, as implied by its capital M. It doesn’t have a subject as such, but we can probably allow a few fragments in conversational English. However, if it’s a sentence, the full stop must go inside the brackets, not outside them. (Sarah Turner of Turner Ink has written a wonderfully concise post explaining these conventions.)

Here’s my ‘technically correct’ remix:

It’s not a glass.

It’s a chalice.

(Made of glass.)

This US counterpart sidesteps all these problems (apart from the capital C) with a punchier single-sentence version that’s arguably more effective. I don’t know which came first, or whether the same agency produced this one.

Who cares?

Isn’t this all ludicrously pedantic? Maybe, but the rules in each case are very clear and not difficult to learn (or Google). And if you don’t get it right for a ten-word slogan on a poster, when do you get it right?

For the sake of an extra word or punctuation mark, it has to be worth it. Short of using obsolescent constructions like ‘to whom’, which might actively confuse the reader, you don’t lose anything by having the grammar right.

Only swivel-eyed pedants like me and Lynne Truss get worked up about this stuff. But I believe everyone is aware of it to some extent, just from reading and listening to language all their lives. While small errors don’t nobble the meaning completely, they may well impair it, or create a negative impression – even if only on a subconscious level.

It does seem strange that no one involved with these ads picked up on these issues. I guess it just proves the old printer’s adage: the larger the type, the harder it is to spot the mistake.

Tags: Plain English, posters, Stella Artois