The madness of QR codes

QR codes have their uses. They’re great for directing motivated, interested readers towards online resources that they might value. But for traditional advertising, I really can’t see what the fuss is about.

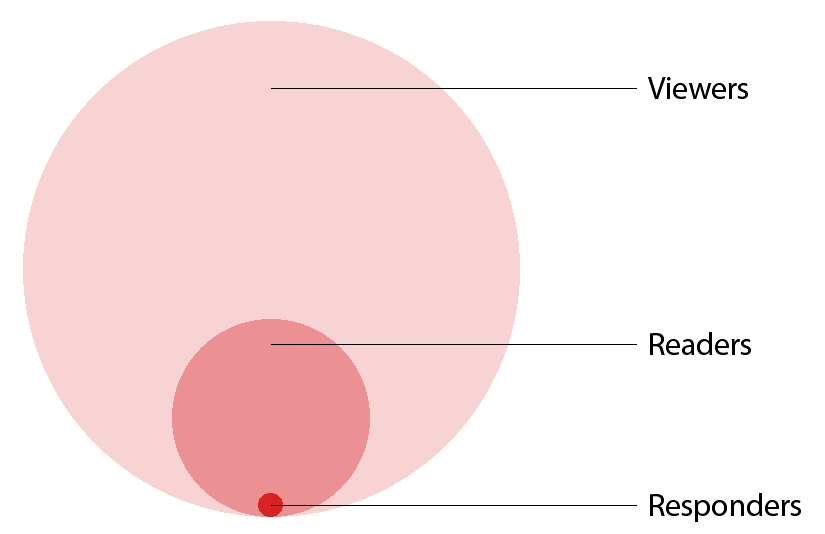

Consider the way a traditional ad works – a poster on a bus shelter, for example, or a display ad in a magazine. We could divide people who interact with the ad into three groups:

- Viewers are simply people who see the ad. They are often quantified as ‘impressions’ or ‘views’. Under the CPM charging model, the advertiser might pay a particular rate for a nominal number of views that their exposure is thought to generate.

- Readers are those viewers who read and digest the ad. The exact number is unknowable, and depends on the power of the ad to attract and hold attention through its creative. Many factors might prevent the reader from grokking the ad in its entirety: inattention, interruption, irrelevance and so on.

- Finally, responders are those readers who actually take action as a result of reading the ad. For the type of ads we’re talking about, the most likely DCR (desired customer response) is a purchase.

The diagram below shows these three subsets in approximate proportion, showing the way they decrease in size as the interaction progresses.

Actual response rates for outdoor and press advertising are hard to gauge, so let’s use the generally agreed average for direct marketing as a benchmark: 3%. So if your ad was seen by 100,000 people, and 3000 made a purchase, you’d probably be satisfied with the result.

The actual figures will vary based on the product, sector, ad location and many other factors, but these three groups will always be there.

Advertising 2.0

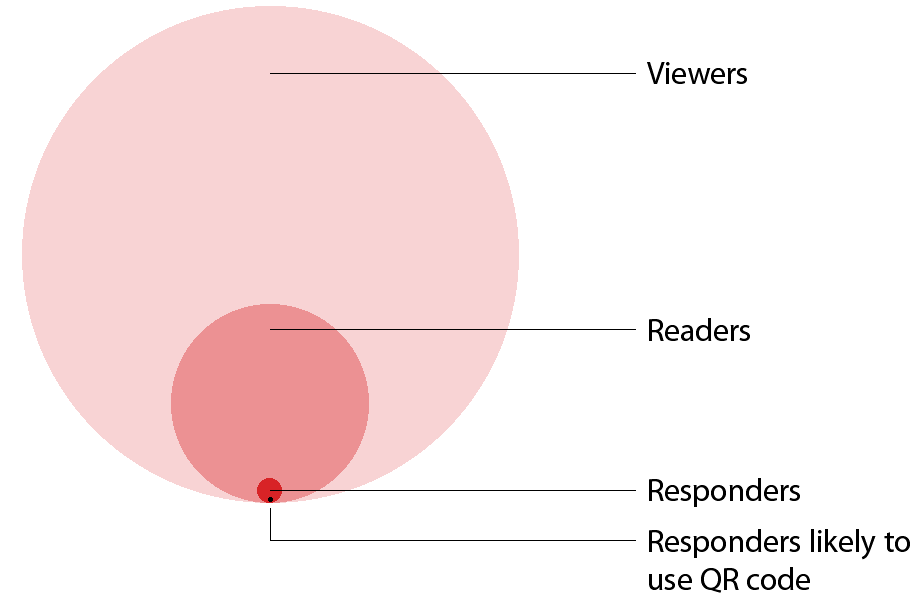

Now let’s consider the same breakdown, but with a QR code thrown into the mix. In addition to the main DCR, we now have a secondary DCR: scanning the QR code in order to visit some sort of online presence.

Unlike the option to make a simple purchase, the option to scan a QR code is not open to everyone. You need a smartphone, you need a scanning utility on your smartphone and (crucially) you need the willingness to get your smartphone out and actually scan the code.

All these factors have the effect of reducing the pool of potential responders – and it is primarily responders rather than viewers or readers we’re talking about, because the ad must still do its job of communicating benefits before anyone will be willing to take action. People are not going to suddenly get interested in an ad because it has a QR code stuck on it.

Stat’s the way

So how many people might we attract with our QR code? Let’s check some stats.

The figures for smartphone penetration are improving all the time, and now stand at nearly 50%. The figures for QR code recognition sound promising too, with 40% of UK consumers now knowing what they are. Actual usage figures, however, are far weaker – just 12% of people have succesfully scanned a QR code.

Twelve percent sounds pretty good as a response rate, but remember that we have to slot that figure into the mechanic of our ad. If our ad manages to turn 3% of viewers into responders, but only 12% of responders actually have the means, motive and opportunity to respond, then the best figure we can hope for is 12% of 3%, which is 0.36%.

So, on average, we can expect about a third of a percent of people seeing an ad to use a QR code. The diagram below gives an idea of the proportions we’re talking about.

Of course, response rates to QR codes will always vary as the result of many factors – the product, its target sector and the strength of the creative that surrounds them. If we’re selling smartphones to under-30 hipsters with black-framed glasses, for example, we might expect uptake to be much higher.

But for other sectors, the QR code will offer only the most marginal utility. For example, just 1% of those aged 55–64 have used a QR code successfully. In the viewer-reader-responder model I’ve outlined, that could reduce response rates to 0.03%, or just 30 responders out of every 100,000 viewers. So if we were selling round-the-world cruises to grey-pound consumers, we’d be well advised to pick a nice appealing photo for the poster, and not rely on anyone QRing themselves online to view our TV spot on YouTube.

Dilution not addition

Given the sacrifices we must make in order to include a QR code – altering the layout of the ad itself, and creating an online presence for the code to lead to – is it worth it?

A QR enthusiast might point out that the QR route isn’t offered instead of the main conversion mechanic, but alongside it. Doesn’t it offer the possibility to generate extra interest, extra sales? Can’t we get the 3% we would have had anyway, and add on the extra 0.36% as a bonus?

The answer is a very cautious, very qualified ‘yes’. We might get some readers to scan – people who are interested in the ad but won’t carry out the DCR because they’re not ready to buy. This is the arena of ‘engagement’ as opposed to (old-fashioned) ‘selling’ – encouraging interaction as a prelude to a sale.

However, the idea that engagement leads to a sale is questionable at best, misguided at worst – read this superb article for a discussion of the arguments against it. A snappier summary is by Ad Contrarian Bob Hoffman:

We don’t get them to try our product by convincing them to love our brand. We get them to love our brand by convincing them to try our product.

But what if our QR scanners are drawn from our 3% of responders, rather than wavering readers? In that case, all we’re doing is cannibalising our own conversions. By offering the QR code as an option, we’re simply diverting readers from the main DCR – getting them to play a Facebook game when they might otherwise have just bought the product, which is (presumably) what we’re trying to achieve. In other words, we’re diluting our response rather than adding to it.

Online playground

From the traditional adman’s point of view, capturing the reader’s attention and then handing them off to some other channel is sheer insanity. Instead of closing down the interaction towards a sale, you’re opening it out by pushing the reader towards an online playground with a million other shiny things to click on. It’s like a salesman getting a face-to-face appointment, then spending it chatting about last night’s TV. For more on the incompatibility between tried and tested ad writing and the QR-code mechanic, see Alistaire Allday’s excellent recent post.

Maintaining interest and commitment across multiple channels can only make things harder and more complex. There’s more creative to do, and it must all be in the right tone. The user experience needs to be smooth and uniform, or people will feel unconsciously ill at ease. Operationally, it’s likely that more agencies (or freelancers working for them) must work together to deliver a seamless result. Basically, there’s more work to do, more balls to juggle and more things that could go wrong.

Muddy waters

Visually, QR codes are terribly obtrusive, adding a distracting new element that clashes with what the copywriter and art director are trying to do. They take up valuable ‘real estate’ that can be used to strengthen the main message. They generate plurality of meaning and, crucially, ambiguity in terms of the DCR. What do you want me to do – visit a branch, or scan this code? Am I missing out on something if I don’t scan it? And how do I know that it will take me somewhere I can trust? What is that weird blocky thing, anyway? (Remember, a whopping 60% of people have no idea what a QR code is.)

Arguably, a URL on an ad also detracts from the DCR. But this is a known, accepted and much less conspicuous convention, with a clearly understood purpose: ‘if you want to know more about us, you can go to our website’.

Then there’s the implied meta-message of including a QR code, which is ‘we’re targeting savvy smartphone users’. As noted, older readers are very unlikely to scan. So they might feel put off just by the presence of the code; it might give them a sense that ‘this isn’t for me’.

Unasked question

It’s notable how few ads have chosen to rely on QR codes as the sole DCR. If they were that powerful, they’d be trusted as the one and only means of response in an ad. Right now, that seems a long way off, and QR-only remains the domain of leftfield teaser campaigns.

For the rest of us, QR codes are the answer to a question nobody asked. Before they happened, I never heard anyone express a longing for a way to automatically ping readers over to their website – particularly one that involves requiring them to take a (slightly weird) physical action in a public place.

Yet because QR codes exist, and seem to fit with fashionable notions of ‘engagement’, they’re being shoehorned into ads regardless. The whole thing is led purely by technology, not customer preferences or psychology. It’s madness and I expect to see it end very soon.

Tags: conversion rate, conversions, QR codes