How to sell like Don Draper

As my Twitter followers may already know, I’m currently watching the brilliant Mad Men from the beginning. (I’m a bit late to the party – season 4 is currently airing in the US.) Central character Don Draper works as Creative Director for Sterling Cooper, a Madison Avenue advertising agency, in the early 1960s, so there’s lots of potential interest for marketing professionals.

Truth be told, however, most of the series is about emotional intrigue and the mores of post-war America, with relatively little about the art of advertising (in the episodes I’ve seen, anyway). But when the focus does move to marketing, the content is fantastic – believable, compelling and thought-provoking. As well as showing the collaboration (and conflict) between different roles within an agency – creative director, copywriter, designer, account handler – Mad Men also has lots to say about the art of marketing, its role in society and the morality of persuasion and selling.

Lighting-up time

When you watch the series, one of the first things to strike you is the incredible prevalence of cigarettes. Everyone smokes in Mad Men: executives, housewives, doctors (in their surgeries), pregnant women. You half-expect to see dogs and cats puffing away on the verandah, bad-mouthing their owners over a Marlboro. Cigarettes are a sort of emotional punctuation mark for the events of the day, both important and trivial.

Given this totemic status, it’s significant that Don Draper’s most pressing task in the first episode is coming up with an ad concept for Lucky Strike cigarettes, one of Sterling Cooper’s most important clients. In 1960, the cigarette industry is beginning to come under fire from health campaigners, backed up by researching showing the link between smoking and cancer. Lucky Strike’s executives clearly regard this as an assault on American values, but the fact remains: cigarettes can no longer be marketed as a healthy option.

Toasting the competition

At the Lucky Strike meeting, junior account manager Pete Campbell floats a radical approach. Citing in-house research into the Freudian concept of the unconscious ‘death wish’, he suggests positioning smoking as the last preserve of the macho man – someone so fearless that he can gamble with his own life. But this proposal is derided by the tobacco executives.

Draper, improvising, points out that they actually have a great opportunity – a level playing-field with equal competing products and the chance to say whatever they want in their marketing. Inviting the Lucky Strike managers to talk about the process by which their product is manufactured, he seizes on the phrase ‘it’s toasted’ as the new Lucky Strike slogan. In fact, all cigarettes contain toasted tobacco, but that’s beside the point. The use of ‘toasted’ aligns cigarettes with homeliness, comfort, warmth and simple food – as far away from poison as you can get.

Don then justifies his approach with this brilliant speech (click here to watch it).

Advertising is based on one thing: happiness. And do you know what happiness is? Happiness is the smell of a new car. It’s freedom from fear. It’s a billboard on the side of a road that screams with reassurance that whatever you’re doing is OK. You are OK.

Emotional currency

‘You are OK.’ Is that what it comes down to? If so, it’s a profound way to think about the effect we’re trying to have with our marketing, or the message we’re trying to get across. Draper is saying that benefits don’t have to be real – or unique. They just have to be emotional, powerful and believable. That’s all. If you can make your prospect feel good about buying, or offer them an escape from their fears, they’re going to buy from you. That’s why marketers can sell people something as harmful as tobacco.

Don’s lesson is clear: deal in the currency with the deepest possible resonance for your audience. Concrete benefits are just material. Ideas are just weightless abstractions. But emotions are real. This is advertiser not as shopkeeper, philosopher or entertainer, but as priest or parent – forgiving, reassuring and blessing. Don’s slogan transforms Lucky Strike from a poisoner into a bastion of comfort against the unsettling forces of change.

Safety first

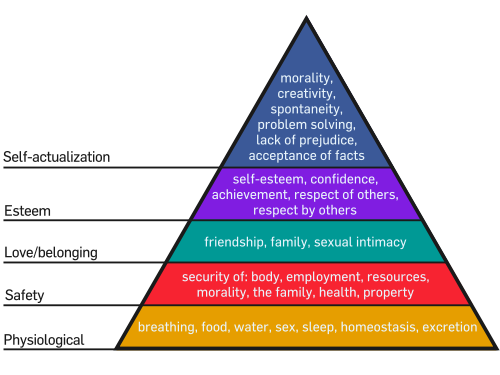

Don’s position is given some psychological ballast by Abraham Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs, shown in the diagram. (Source: Wikipedia.)

The needs are often presented as a pyramid to show that each level supports the one above it. The theory is that as each successive level of need is satisfied, the next highest level takes precedence. At the lowest level is physiological need – the need to carry on living, to persist as a being. After that, safety is the number-one concern. Although we’ll aspire to esteem and self-actualisation given the chance, we won’t even think about those higher levels of need if our safety isn’t assured.

Don’s slogan for Lucky Strike is a masterstroke because it outmanoeuvres the health lobby’s attack on this level. If consumers don’t believe that cigarettes are safe, it doesn’t matter how much you appeal to higher levels of the hierarchy, such as esteem (Campbell’s tack with his ‘death-wish’ creative). Don sees that people need to feel safe before that can even think about wanting anything else, such as impressing their peers.

In reality, smoking threatens consumers on a physiological level. But acceptance of facts is at the pinnacle of the hierarchy, and we’re not in the realm of rational analysis – we’re talking about appealing to an audience at the most basic emotional level possible. (Or, it could be argued, manipulating them in the most cynical way possible.) However illogical it might seem, cigarettes that are seen as safe will sell (in 1960, at least).

Higher love

Earlier in the same episode, when he’s casting about for ideas, Don interrogates a waiter about his allegiance to Old Golds as opposed to any other tobacco brand. He doesn’t really get any useful feedback from his ad hoc research, suggesting that brand loyalty is something that needs no justification – at least, not consciously. The nearest he gets to a ‘reason’ is the waiter’s stubborn affirmation that he loves smoking. Thoughtfully, Don writes ‘I love smoking’ on a napkin.

As the needs hierarchy shows, love and belonging are one level up from safety – so they won’t have power to persuade unless safety needs are satisfied. But, conversely, love is more basic and powerful than other more intellectual concerns such as confidence or creativity. We want to be loved more than we want to make choices, or to be clever.

Of course, the love we feel for a cigarette, or any other product, isn’t the same as the love we feel for another human – and they can’t reciprocate. And yet people clearly do get very attached to things, investing emotion in the inanimate – houses, cars, iPods. The book that I used to give up smoking was at pains to point out that ‘cigarettes are not your friends’. For committed smokers, tobacco is a lot more than a product – it’s an ally to turn to when things get rough.

Deeper engagement

Recently, I’ve been writing a suite of case studies for a B2B company. They make a software application that their clients can use to run pretty much every aspect of their businesses. Often, adopting the software literally transforms working life, sweeping up dozens of bitty administrative tasks into a single interface.

During interviews, some of the clients have told me, spontaneously, that they ‘love’ the system. Of course, the first thing they say is it that helps them solve practical problems (the top level of the hierarchy) or achieve on a personal level (second-from-top level). But as the conversation progresses, we get down to their true level of engagement.

For me, that suggests that, even in the dry world of B2B, copywriters and marketers could talk about love a lot more than they do. Personally, I often try to include the word ‘love’ in my copy (e.g. ‘You’ll love working with us’). However, I often find that my clients are unwilling to approve it.

Perhaps they’re uncomfortable with plumbing these depths, since marketing activity is often more about self-actualisation for the sellers (creativity, problem-solving) than building relationships with buyers. But it’s no good offering abstract, high-level benefits if your prospect doesn’t feel safe or loved. We should never be afraid of addressing the audience’s most basic needs before we elaborate on the higher-level benefits we can offer them. After all, that’s what Don would do.

Tags: cigarette marketing, Don Draper, Lucky Strike, Mad Men, Madison Avenue, Pete Campbell, Sterling Cooper